Bohol: The Story of Place

Known for its iconic Chocolate Hills, ancient churches, the historic Sandugo blood compact, the endemic tarsier, and pristine beaches, Bohol represents both the Philippines' natural heritage and its complex cultural evolution.

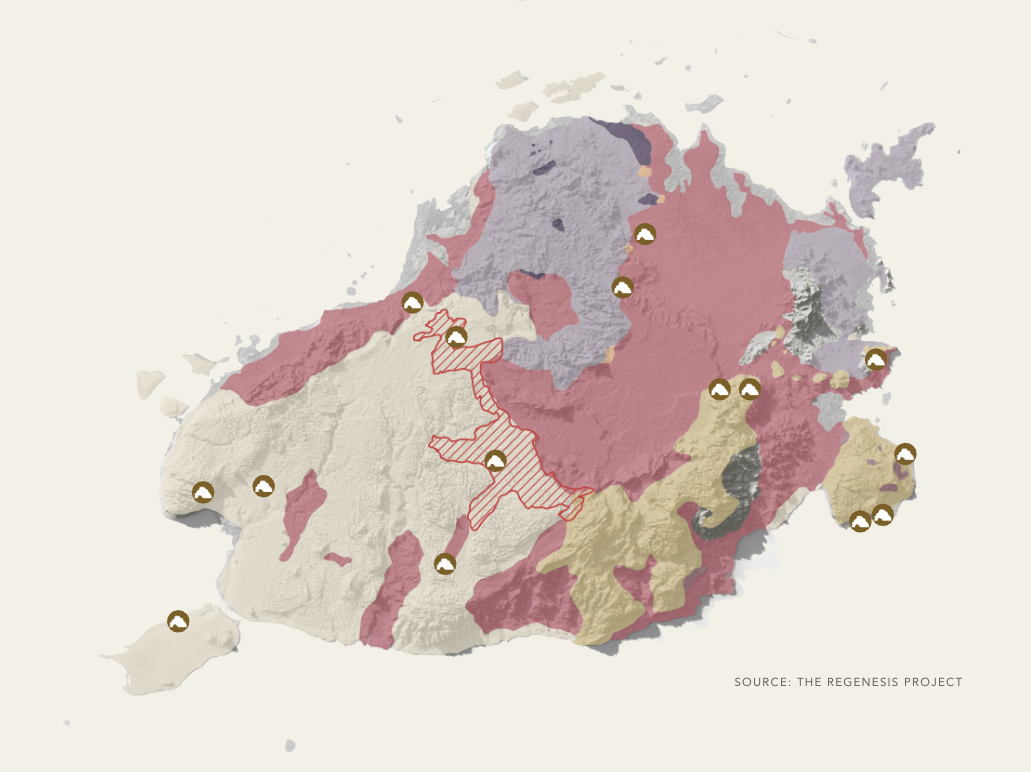

Geology: A Predominantly Karst Landscape

Born from Ancient Reefs

Bohol's story begins underwater. Like much of the Philippine archipelago, the island was slowly pushed upward from beneath shallow tropical seas through volcanic upheavals over thousands of years. As the sea floor emerged, it exposed layers of coral and calcium carbonate sediments that rainwater—acidic from atmospheric carbon dioxide—carved into the island's distinctive landscape.

This geological process created Bohol's defining features: 50% of the island consists of karst topography, explaining the extensive cave systems that earned it the name "Cave Country." The same forces that created the famous Chocolate Hills also formed 114 springs, 172 creeks, and 4 major rivers including the Loboc and Inabanga.

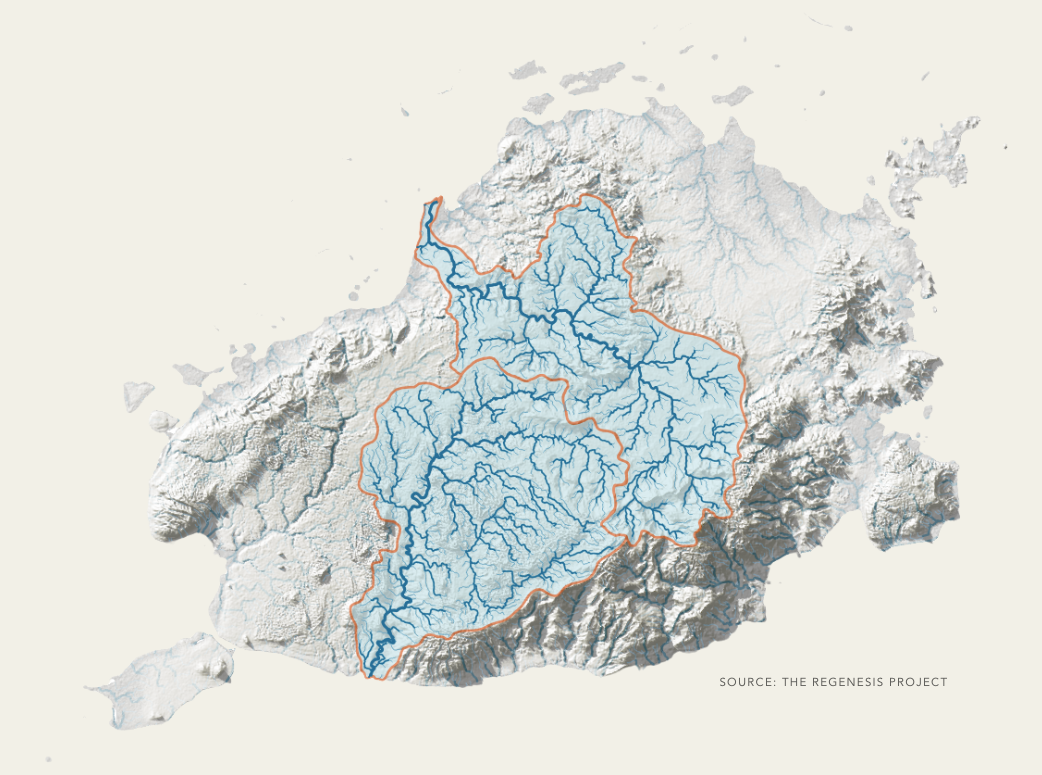

Hydrology & Watersheds

The Karst Paradox: This limestone landscape creates both abundance and scarcity—rich clay soils and numerous springs, but also high porosity that means water can disappear during dry seasons. Historical records show both devastating floods and severe droughts, including major flooding events in the 1800s and drought periods in 1966, 1979, 1987, and 1991-1992.

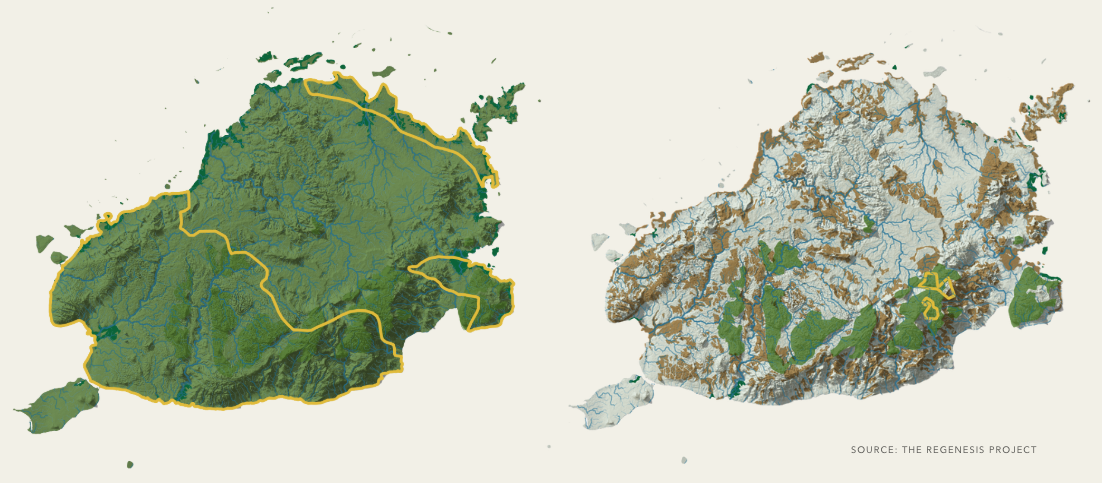

Hill to Reef: A Complete Ecosystem

Bohol's compact "hill to reef" topography creates extraordinary biodiversity. From karst forests covering interior hills to riverine wetlands to coastal mangroves and coral reefs, these connected ecosystems support species found nowhere else—like the endemic tarsier.

The island's extensive coastline and shallow shelves, including the only double barrier reef system in the region, make it a marine biodiversity hotspot within the Coral Triangle. When the island fully formed, former land bridges became coral-rich tidal zones that provided year-round food sources for early inhabitants.

Terrestrial Ecosystems & Biodiversity

Marine Ecosystems & Biodiversity

People of the Waters

Early Boholanos were quintessentially maritime people, settling along coasts and rivers where fishing provided primary sustenance. Communities organized into autonomous barangays led by datus and baylans (spiritual leaders), following lunar planting calendars aligned with monsoon cycles.

These were deeply spiritual people who recognized sacred sites—rivers, caves, springs—as homes of anitos (nature spirits). They maintained elaborate ritual cycles honoring these spirits through offerings and ceremonies, understanding their lives as interconnected with natural rhythms.

Pre-Colonial Settlements

The Sandugo: First Encounter

Spanish conquistador Legazpi wasn't meant to land in Bohol—hostile encounters elsewhere drove his ships to seek shelter in Hinawanan Bay. On March 25, 1565, Datu Sikatuna and Legazpi entered the historic Sandugo blood compact, the Philippines' first recorded treaty of friendship.

Spiritual Transformation

When Jesuit missionaries arrived in 1596, they found Boholanos eager for baptism, practicing Christianity with remarkable devotion—perhaps because they were already deeply spiritual people. The reducción system concentrated populations around churches in towns like Baclayon (home to the Philippines' oldest stone church), Loboc, and Inabanga.

From Anitos to Fiestas: Traditional rituals transformed into elaborate town fiestas honoring patron saints. Bohol became one of the Philippines' most fiesta-obsessed provinces, with May bringing a "reverse diaspora" of Boholanos returning home for celebrations that blend sacred and social dimensions.

Spanish Regime: Colonial Settlement Patterns

Modern Crossroads: Opportunity and Threat

Today's Bohol stands at a critical juncture. Tourism has boomed with improved ports, the Bohol-Panglao International Airport, and international visitors discovering the Chocolate Hills and world-class diving. Yet this success creates new challenges.

Landscape Under Pressure: Logging concessions caused widespread deforestation, with native species like molave, narra, and lawaan replaced by introduced trees. Upper watersheds became degraded marginal land. Traditional cottage industries that once utilized abundant natural materials—bamboo, rattan, nipa—now face resource scarcity.

Ecological & Cultural Degradation over Time

Tourism's Double Edge: While generating vital revenue, mass tourism threatens to replicate Panglao's over-commercialization in pristine areas like Anda. The interior remains underdeveloped but faces development pressure despite protected area status.

Mass Tourism

Infrastructure vs. Nature: New developments threaten the delicate balance—unnecessary "flood control" projects concrete natural rivers, the planned Cebu-Bohol bridge will increase development pressure, and real estate developers eye the island for large-scale projects.

The Regenerative Imperative

Bohol's designation as a UNESCO Global Geopark recognizes its geological significance, but protection requires more than designation. The challenge is finding balance: how to honor both the 500-year-old churches that represent cultural heritage and the 50-million-year-old landscapes that shaped the island's identity.

The island's "hill to reef" geography that once provided abundance can do so again—but only through regenerative approaches that work with, rather than against, the karst landscape's natural rhythms. The question facing Bohol is whether it will become another victim of extractive tourism and development, or demonstrate how islands can thrive by restoring the ecological and cultural foundations that made them special in the first place.

This is why Bohol matters beyond its borders: as a living laboratory for proving that complete island regeneration is not only possible, but essential for authentic prosperity that honors both people and place.