Adaptable Spaces

Role of Transient Structures and Spaces in the Response to a Pandemic (and other Emergencies)

Covid-19 has upended urban life as we have all known it. It has been many things; amongst which the crisis for healthcare space has been severely exacting. In the past, we have mostly encountered ‘bang’ events like natural calamities or terror attacks. Their fallout is a sudden demand for large spaces to provide shelter and medical aid. However, these events are contained to a location and the number of affected is predictable. The pandemic has posited a vastly different situation wherein there is a relentless swell in the number of people requiring medical attention across the globe. Emergency and medical parlance define this as a ‘surge’ event. There has been more than eight million people who have tested positive (accurate up to the time of writing) of which more than 3.5 million are still in some form of medical shelter receiving treatment (1) . This is creating an immense strain on emergency resources, particularly space to provide for these affected.

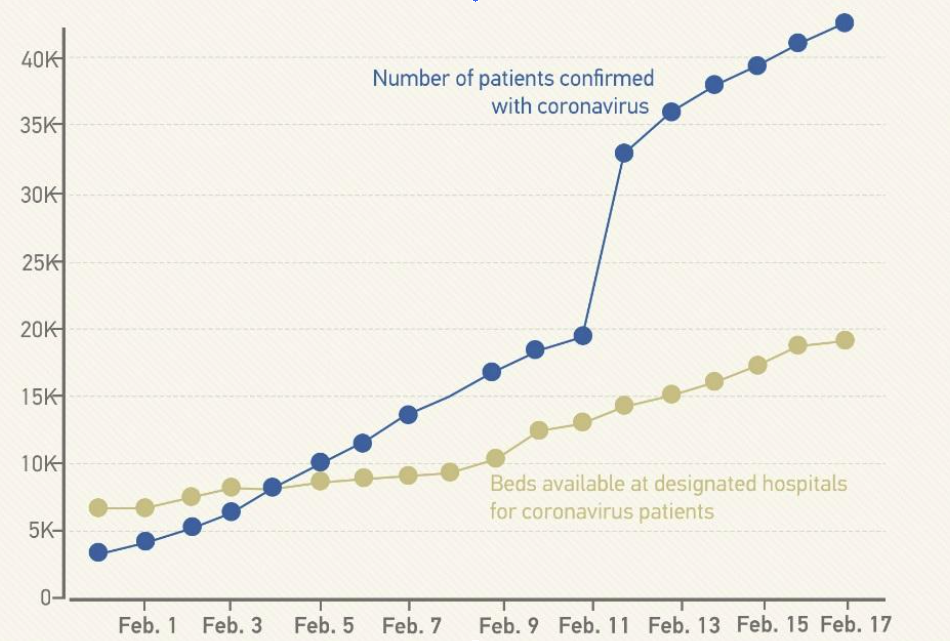

Stochastic models to estimate a trend to aid in planning the course of response have yielded low success. Most cities have thus been overwhelmed. Image 1 shows the trajectory of the community spread and its gap to available healthcare space in Wuhan, China where the pandemic originated. (Note that the gap depends on the criteria individual governments have instituted to admit affected people to medical care facilities. Japan for instance, had advised mildly ill people to remain at home to reserve the healthcare spaces for those in severe condition. (2) )

The highly contagious nature of the flu-pandemic further exacerbates this space demand. Besides patients, there is also a large proportion of the community that needs space to be kept safe in isolation for certain periods. These could be close contacts of patients, healthcare staff working in rotating shifts, or affected migrant populations like in India and Singapore. Furthermore, all such facilities need to adhere to strict guidelines with respect to spacing between beds, containment zones, triage areas etc. which all require greater space. Authorities have been hastily converting various types of spaces and adapting them as best as possible to keep pace with the demand.

Image 1: The graph shows the spread of infection versus available hospital space in Wuhan, China within the first three weeks of the lockdown ordered on 23rd January,2020.

(Source: CGTN and NHC, Wuhan Health Commission (3) )

Creating Transient Capacity within Hospitals

Hospitals have adopted all means necessary to free-up space, especially intensive care spaces. This has been done by cancelling or deferring elective procedures and non-critical admissions, re-opening closed units and converting hallways, operating rooms, recovering rooms to treat Covid-19 patients. Antonio Pesenti, head of the Italian Lombardy regional crisis response unit which was one of the worst affected areas in Italy, summed-up the situation - “We’re now being forced to set up intensive care treatment in corridors, in operating theatres, in recovery rooms. We’ve emptied entire hospital sections to make space for seriously sick people.”(4)

Image 2: Corridor equipped with hospital beds and equipment at the University Hospital (CHUV) in Lausanne, Switzerland, 31st March, 2020.

(Source REUTERS)

Converting non-healthcare facilities:

Termed as Alternative Care Sites (ACS) (5) , these follow the standard practice of making use of certain large capacity non-healthcare facilities to provide shelter. For the pandemic, they are being re-purposed as patient care sites which are not equivalent to hospitals. Yet they can significantly bolster a city’s capacity to care for non-critical cases and relieve the pressure on hospitals to serve those who need intensive care. Various agencies across the world (like the World Health Organization, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the American Institute of Architects amongst others) have been devising specific set of guidelines to help authorities and industry practitioners to swiftly re-purpose these spaces for (6) :

Patient isolation and as alternative to home care for infected patients;

Limited supportive care for noncritical infected patients;

Care for recovering, noninfected patients;

Quarantine of contacts of confirmed cases;

Primary triage and rapid patient screening;

The most common spaces being converted to such ACS are:

Large Assembly Spaces like Convention Halls:

Their expansive floor spaces offer flexible configurations which can be swiftly re-configured and expanded. They are also served by efficient logistic systems for quick service and delivery. However, their centralized ACMV systems do need to be tweaked to ensure the necessary pressure differentials and proper extraction systems to prevent spread of the virus from contained areas. Examples include the Singapore Expo, Chicago’s McCormick Place, New York’s Javits Centre, Rio Centro Convention Centre in Rio de Janeiro amongst many.

Image 3: Emergency patient care units set-up inside the Rio Centro Convention Centre in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

(Image Credit: Antonio Scorza, Shutterstock)

Hotels/ Student Residences:

Asian countries were prompt from the onset in enlisting the support of city hotels and student residences in the universities to become quarantine centres for housing patients with mild symptoms, recovering patients, close contacts of confirmed cases as well as healthcare workers. With individual rooms complete with en-suite toilets, hotels have been ideal places to house affected people in isolation. The constraint being their limited capacities which cannot be expanded. In the US, the American Hotel & Lodging Association is assisting by creating a national database to connect hotel properties with the health community to help them meet their growing demands (7) . AirBnb too launched its Frontline Stays program in several countries to allow subscribers to offer their places to accommodate medical and health professionals (8) .

New Hospitals:

Wuhan’s response to the pandemic encompassed efforts to create all such transient facilities to shore up its capacity. By mid-February 2020, the Government had already designated over 40 hospitals to cater only to Covid-19 patients while more than 20 venues including gymnasiums, exhibition and sports centres, together with hotels and schools, were re-purposed into temporary hospitals (3) .

Image 4: Snapshot of all the transient facilities set-up in Wuhan within the 1st three weeks of the lock-down.

(Source: CGTN and NHC, Wuhan Health Commission (3) )

Yet, none of these transient facilities were sufficient or equipped to treat patients requiring intensive care. This necessitated the erection of two new temporary hospitals. The 1,000-bed Huoshenshan Hospital and the 1,600-bed Leishenshan Hospital were built and completed within a span of 10 to 12 days to treat patients in critical condition and relieve the pressure on the existing hospitals (3) . These two hospitals represent amongst the largest and best equipped new temporary hospitals erected specifically to treat Covid-19 patients. The speedy construction was made possible by using pre-fabricated modular units which were placed into steel skeletons above concrete foundations and then fitted out with necessary medical infrastructure (9) .

Image 5: Image showing modular parts being slotted in to erect one of the two new hospitals in Wuhan, China.

(Source AFP)

Other examples of new purpose-built hospitals mostly include field hospitals of varying capacity in New York City’s Central Park, Sao Paulo’s Pacaembu Stadium and several others in Italy, Turkey, Spain etc. These are all being erected using tented structures and often aided by military units who are more familiar with such quick temporary set-ups.

Image 6: Tented structures erected inside Sao Paulo’s Pacaembu Stadium to serve as a field hospital.

(Image Credit: Caio Paderneiras, Shutterstock)

In Singapore, the greater challenge has been to decongest the hundreds of Foreign Worker Dormitories (FWD) which house more than 323,000 (10) low-wage migrant workers in often cramped closed-quarter living conditions. These dormitories have become the epicentre of the pandemic in the city state with more than 90% of the Covid-19 cases being from these FWDs (11) . While the government is using hotels, military camps and vacant public housing blocks as immediate alternative accommodations, works have commenced on the construction of several new “quick build dormitories” on vacant land plots (12) . These are being built using modular construction techniques and following revised guidelines aimed at providing spacious and healthier living conditions. Modular construction has also been necessitated by the acute shortage of manual labour owing to strict quarantines enforced on the existing FWDs.

These measures broadly sum-up the global effort to quickly create emergency medical space. It has been particularly reliant on requisitioning different types of non-traditional space and adapting them using modular technologies and structures to create transient spaces. This situation has however revealed that there is a significant potential for cities to expand within itself to counter such a crisis. While packing patients into hospital corridors and creating endless rows of partitioned cubicles inside convention halls provides one version of such capacity, it fails to create a tenable environment for a very ailing group of people (including the tirelessly working medical professionals). A far better version would need cities to look at its shared spaces and certain infrastructures with a reformed approach to create this buffer capacity. This will need to be combined with existing and new pre-fabrication technologies to quickly erect or transform these spaces to be effective and tenable to serve alternative functions.

Making Open Spaces More Available and Accessible:

An equitable distribution of public open space has always been identified as a key feature of a resilient city. During normal times, they contribute to providing access for all city resident to shared amenities and Nature; while during emergencies, they can buffer the city against impact. The Sponge City initiative in China is an example of large public parks built to absorb surface runoff water and disperse it back into the environment, thus reducing the risk of urban flood and mitigating the effect of drought.

During this pandemic, places like NYC’s Manhattan, Wuhan, Singapore have been able to make use of available spaces to swiftly erect emergency structures, be it tented or otherwise. Planning such spaces with the ability for them to readily plug into the city’s network of vital infrastructure like access roads, water, electricity and sewers could further expedite their ability to be operational within a shorter time-frame. In peace-time, scenario-based modelling in-tandem with modular designs could be used to pre-plan these structures with all necessary considerations including that of creating spaces that are less hostile and more salutogenic in nature.

Streets too are being looked through a different lens as teleworking promises a potential upheaval in commuting patterns. Milan, in Italy’s Lombardy region, became one of the first cities in the world to announce permanent changes to widening its sidewalks and reducing vehicles. The ‘Strade Aperte project’ unveiled on 21st April this year, proposes major transformations to create better open spaces and pedestrian realms in the city. “We worked for years to reduce car use. If everybody drives a car, there is no space for people, there is no space to move, there is no space for commercial activities outside the shops,” says Marco Granelli, the city’s councillor for mobility (13). Oakland in the US is also transforming 10 percent of its streets into public promenades (14). Likewise, several cities are looking at making such changes permanent in view of the long-term goals to create healthier and lesser pollutive cities. Meanwhile in cities where formal sidewalks don’t always exist, like India, people have been forced to appropriate space from the streets during this pandemic (image 7).

Past epidemics have also led to revolutionary changes in cities. Malaria, erroneously believed to have been caused by poor ventilation, inspired Frederick Law Olmsted’s designs for Central Park in New York and the Emerald Necklace in Boston, among each city’s generous offering of public spaces. In Barcelona cholera epidemics, helped to create the vast grid of abundant of open space for the city to breathe and expand when it needed to (14) . To illustrate this further in the current context, there is evidence to suggest that overcrowded conditions with little access to open spaces has helped Covid-19 to spread rapidly. In New York City, for example, infection rate in the outer boroughs, and suburban Westchester and Rockland counties is almost triple the rate per capita than those in Manhattan (15) . The same is true for Mumbai where the tightly packed slum of Dharavi is amongst the worst affected areas (16) .

Image 7: Social Distancing measures have forced pedestrians to reclaim the streets as shared open spaces.

(Image Credit: Manoej Paateel, Shutterstock)

Planning for Adaptive Use of Spaces:

Planning with the intent for adaptive use in alternative scenarios will create another reserve of buffer capacity. In 2012, the Rambam Medical Centre in Haifa Israel, built a 3-storey underground facility. It serves as a parking lot for 1400 vehicles during peacetime and can function as a 2000-bed hospital in times of emergency (in the context of large-scale military events) to service the entire northern region of Israel. Most of the equipment like beds, oxygen tanks, dialysis machines and others are stored within the walls (17) . Similarly, the Rush University Medical Centre in Chicago, completed in 2012 in the aftermath of the 9/11 attack, was planned to cater for surge capacity resulting from large-scale industrial accidents, bio-terror attack, or pandemic outbreaks. It is now being used effectively in the fight against Covid-19 in the city (18) .

A future with potentially more teleworking will raise questions on the raison d'être of large expensive swanky office spaces and seek ideas for their alternative use. It may provide an opportunity to infuse a mix of shared amenities, residences, short-term stay options etc. to commercial districts of the city. Notwithstanding how the real estate landscape evolves, it’s clear that cities will greatly benefit from flexible and adaptive use plans for future crises. Flexibility in design will surely prove essential to creating make-shift emergency facilities, reorganizing our homes to be better suited for working remotely and even more. Cities could even make such requirements pre-requisites for construction approval for certain critical types of facilities? (9) This will create a reserve of emergency spaces which are better equipped and designed to be quickly operational.

Image 8: Hospital beds are placed in the parking lot set up for the media at Rambam Medical Centre. The space is also equipped with unique filters and air-conditioning systems for protection from biological and chemical warfare.

(Source REUTERS)

Stepping Up Adoption of Modular & Pre-Fabrication Technologies:

As with other emergency events, the most pressing need from the building industry during this pandemic has been the swift erection of emergency facilities like hospitals, quarantine centres, testing sites, etc. The go-to response has been to use various types of modular and pre-fabricated construction techniques. These methods of construction have been mooted by the industry for many years now, primarily for speed, as well as other advantages. It ensures better quality of construction, it is leaner in processes, labour and use of material (and waste), and above all it enables re-use thereby extending the life-span and purpose of the structure. Yet it’s rate of adoption has been moderate at best.

The pandemic has necessitated these technologies and revived the opportunity to propagate them further. Emergency response units could be pre-fabricated as standardized components in factories – as ICU units, triage units, etc, packed into modular units, transported to a location in any part of the world and quickly assembled. Once the pandemic is over these could either be dis-assembled and stowed to await deployment when a disaster strikes again; or the structure should be robust enough to continue serving as a shelter or hospital. China’s ability to build fully equipped new hospitals was based on its planning and preparation following the 2003 SARS outbreak. The two modular hospitals in Wuhan were modelled based on the Xiaotangshan Hospital that was set-up in Beijing within 7 days during the SARS outbreak. It employed a lot of modular and pre-fabricated construction techniques (19). While the Xiaotangshan Hospital was abandoned as it wasn’t fit for re-use or continued use (19) (20) , the new Wuhan Hospitals will be dismantled for reuse. Mr Tian Xiao Tao of House Space Prefab (which was involved in the construction of the two Wuhan Hospitals) says “Once they’re dismantled, they can be reused. They can be transported by truck to other cities where they’re needed. We can also recycle the steel and other useful materials used in the flatpack houses and we can sell them back to factories.” (21) Several designers and fabricators are already working on other modular templates. Italian architect Carlo Ratti’s CURA (acronym for “Connected Units for Respiratory Ailments” and also “Cure” in Latin) model is a 20-foot container repurposed as an ICU. These have already been deployed in Turin. It’s as fast to set-up as a hospital tent and as safe as a regular isolation ward. Multiple units can also be put together to scale up the capacity (22) .

Image 9: Prototypes of CURA have been installed in Italy (Like this Hospital in Turin) where it’s serving Covid19 patients.

(Image Credits: Max Tomasinelli)

Could we possibly look at extending this notion of building quickly and affordably not just to emergency relief structures but also to creating less costly, quickly built buildings in general? Building affordable housing, schools, medical centres etc could benefit millions of people living in places without such basic provisions; not-to-mention the impact it shall have on the use of materials, energy and waste generation. In the same vein, we should look at the efforts to making cities resilient for future epidemics, as measures also to making cities resilient against other existing challenges as well. With more than 6 billion of us residing in urban areas by 2050 (23), cities are and will continue to be the centre of life on earth. However, the design of cities and how they will be inhabited, will determine the threats we shall face or avoid. Covid-19 has further exposed the shortcomings in cities together with the underlying socio-economic disparities. While there will certainly be the tendency for us to fixate into resolving this singular issue in isolation; it is instead paramount that we are cognizant that all our efforts in the post-pandemic period must find commonality of purpose to tackle the challenges that already exist and avoid new ones in the future.